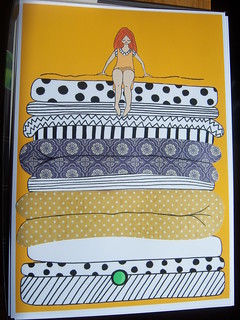

I have felt an affinity to the Princess who can feel the pea under all the mattresses in her bed. When I read David J. Keuler's article, When Automatic Bodily Processes Become Conscious: How to Disengage from "Sensorimotor Obsessions", I recognized myself. Here is Keuler's list of examples of Sensorimotor Obsessions:

- breathing [whether breathing is shallow or deep, or the focus is on some other sensation of breathing]

- blinking [how often one blinks or the physical requirement to blink]

- swallowing/salivation [how frequently one swallows, the amount of salivation produced, or the sensation of swallowing itself]

- movement of the mouth and/or tongue during speech

- pulse/heartbeat [awareness of pulse or heartbeat, particularly at night while trying to fall asleep]

- eye contact [unlike social anxiety-based concerns, this form involves awareness of the eye contact itself or which eye one is looking at when staring into the eyes of another person]

- visual distractions [e.g. paying attention to “floaters”, the particulate matter that is drifting within the eye that is most visible when staring at a blank wall or awareness of subtle movements of the eyes, such as saccadic eye movements]

- awareness of specific body parts [e.g. perception of the side of one’s nose while trying to read or, as in the cases of a young boy and older man, a hyper-awareness of particular body parts such as their feet or fingers respectively]

My health anxiety is linked in part to assuming what I am aware of is dangerous. Floaters in my field of vision were particularly hard to deal with because I was afraid it was serious, and then when the doctor said it wasn't, I was worried I'd be aware of the bits of gray squiggles forever, and haunted by them, and I obsessed about obsessing. Bladder sensations took up a lot of my mental space from an early age.

Keuler proposes treatment consisting of:

- Helping the sufferer understand that awareness of automatic body processes is not dangerous

- Exposure to the sensation and prevention of responses such as distraction.

- Body Scan and Mindfulness, and learning to observe sensations without judgement(Jon Kabat-Zinn has detailed instructions for doing a body scan. I did them everyday for many years, and it helped expand my focus.)

He suggests post-it notes with reminds of the sensation in strategic locations, practicing inviting the sensation in rather than fleeing from it, which ultimately leads to less sensitivity to the sensations and/or greater tolerance of them. Before you panic at the thought of purposely evoking sensations you'd rather banish forever, remember that in actuality you can't perfectly set up the world to never remind you of your breathing, your tongue or your bladder.

I know that bliss when a sensation recedes and the agony of something reminding me of it, but it's the jolt of encountering the feeling reinforces the anxiety, making me wish I could ratchet down my life even more so that I never get surprised. It was liberating to discover that I could purposely face the sensation, and not have to tiptoe around my life.

Apt cartoon by xkcd, about tongue awareness.